Introduction

Since the beginning of the Cold War, NATO’s extended military presence has been broadly located in Northwestern Europe. Much of its military logistical infrastructure is located in the English tidal range, consisting of European coastal areas such as Rotterdam, Antwerp, and Kiel. For most of its 75 years of existence, the tidewater areas served as NATO’s principal hubs for its military infrastructure and reinforcement nodes in the event of a conflict with the USSR whereby the Fulda gap military scenario for Soviet forces overrunning Western Europe from East Germany significantly affected NATO’s planning and defensive strategy.

Over time, the end result of NATO’s strategy led to an over-concentration of resources and infrastructure into one geographic section of Northwestern Europe. Consequently, the bulk of NATO infrastructure and its administrative posture became located in Belgium, such as the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE), which is also intermixed with the vast European Union bureaucracy in Brussels. This in turn has tainted NATO strategic thinking over threat perceptions arising in the East where many of the new frontline member states shared far deeper concerns over the Russian threat than those in the tidewater regions.

Since the Russian invasion and occupation of Crimea in 2014, and more recently after its offensive into Ukraine in February 2022, the United States has sought to shore up NATO’s military infrastructure in Eastern Europe to keep pace with developments to improve its mobility and defend its eastern approaches by investing $8 billion of its financial resources through the European Reassurance Initiative (now known as the European Deterrence Initiative or EDI). Enhanced runways and storage facilities were hallmarks of this programme.

As a result of its investment, NATO is slowly altering its posture toward the East after realizing that the roads and infrastructure required to fight a war in Central and Eastern Europe, namely in Poland and the Baltic states, and even in Romania, sorely lacked the infrastructure among its eastern member states to adequately project power to the East. While Ulm and parts of the Rhine were the centerpiece for NATO staging areas, just as they were during the time of Napoleon, the Atlantic Alliance has only incrementally expanded its logistical and aerial footprint to improve its ability to counter the threat to NATO’s new European borderlands.

Despite these efforts, there is a vested interest within NATO to keep its vast administrative apparatus located in the tidal regions in Western Europe, which simply defies military sense. Together, the ‘tidewater’ dimension of NATO’s geography has tainted the strategic thinking of NATO policymakers, creating a major gap in ‘center field’ to use an American baseball term between the hub of NATO in the coastal tidal range and the actual Russian threat emanating several thousand miles to the East in and around the Black Sea. This has created a major disconnect in perceptions and outlook within NATO as the Eastern European countries regard themselves as part of the frontline against Russian expansionism.

The United States has sought to narrow the gap between the ‘tidewater’ and the ‘frontline states’, by investing in its military infrastructure in Eastern Europe to enhance its mobility since 2016 through the EDI. During this time, NATO sought to improve its warfighting capabilities to deal with a conflict emanating from its two flanks – the Baltic and Black Seas, or what some experts refer to as the two Bs. On the far eastern end of that flank the US has established a new ‘Ramstein in the East’ at the Mihail Kogalniceau (MK) airbase in Romania. While MK has provided NATO with an adequate platform to fend off Russian intrusions from the Black Sea, it is nearly 2,300 km from its command structures, such as NATO Allied Joint Forces Command at Brunssum The Netherlands and the Romanian theatre in the Black Sea, a vast aerial arch that stretches across a region once part of the former Austro-Hungarian empire. In between are what former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld described as the ‘Lily Pads’ to describe the wide swath of Eurasia and the former Soviet Union consisting of former Soviet airfields that the United States could utilize in a future conflict.

Unfortunately, NATO’s footprint in the Carpathian-dominated East is light in the points in between the ‘old’ and ‘new’ Ramsteins. What is needed is perhaps a mini Ramstein located somewhere in between, and the civilian airfield at Ostrava, CZE could be part of that solution. Ostrava could help ensure access to the Eastern flank despite any military or political challenges. For example, Germany’s AfD party is opposed to German support for Ukraine and has questioned German membership in NATO and could undercut Ramstein as the major aerial hub in Europe.

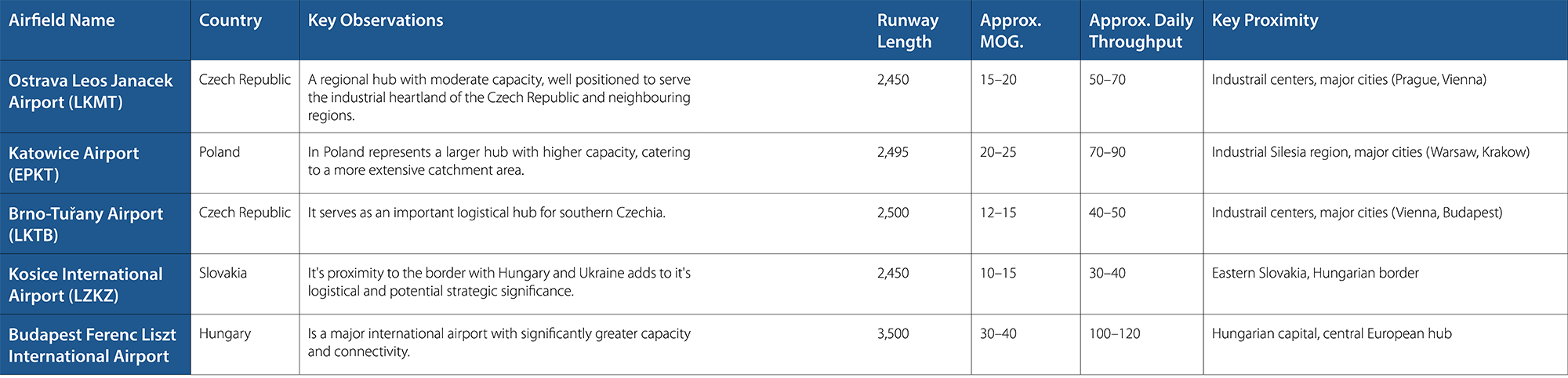

Key Airfields in Eastern/Southeastern Europe: Contextualizing Ostrava or A comparative overview of critical airfields with assessments based on runway length, MOG (Maximum on Ground) capacity, daily throughput, and proximity to strategic locations. © Copyrighted

Fresh thinking is required in the minds of NATO planners over how to reinforce its presence in the East in the areas between Europe’s tidewater and the Black Sea. When airpower strategists think about the areas in between the tidewater and the Black Sea, few Western experts think about the importance of Czechia and its strategic location.

Led by President Petr Pavel, Czechia is making major investments in military rearmament after years of neglect. It is modernizing 50 percent of its military and spent $7.5 billion to purchase two squadrons of F35 fighters. While Čáslav airbase will be the home for two of Czechia’s recently acquired F35 squadrons, the civilian airfield at Ostrava deserves closer attention as a new forward base for NATO airpower given its proximity to Ukraine and its rail connections on an east-west, north-south axis with the rest of Eastern Europe.

Ostrava: A NATO Window on the Carpathians?

Situated in Moravia and the gateway to Silesia, the former steel town of Ostrava represents one of a handful of airfields in Eastern Europe that is capable of handling B52H Stratfortresses. As the ‘Pittsburgh of Czechia’, Ostrava is strategically located at the confluence of four rivers (Odra, Opava, Ostavice, Lučina) and is well positioned geographically to project NATO beyond the Carpathians.

As an example of its prominence, Ostrava’s annual air show has risen to become one of the largest in Europe. Since being launched in 2001, the NATO Days air show in Ostrava has become the ‘Farnborough of Eastern Europe’, and attracts several hundred thousand visitors from Czechia and surrounding countries each year.

In 2015, attendance reached an all-time record of 225,000 visitors, elevating it as one of the largest European air shows in terms of attendance. The NATO days in Ostrava air show is also one of NATO’s largest public diplomacy events organized in Europe. In 2023, the air show attracted approximately, 183,000 spectators. The air show involved the participation of several NATO member nations, including the United States Air Force, which dispatched B52 Stratofortress aircraft to participate in the air show – an unmistakable diplomatic statement of the US’s interest in the strategic importance of the airfield. The civilian-operated airfield at Ostrava has one of the longest runways in the Czech Republic and certainly ranks as one of the top airfields east of Ramstein. While the airfield is operated by a civilian company, the Czech Ministry of Defense has the ability to use the airfield and is working on an arrangement to gain greater access to Ostrava for military purposes.

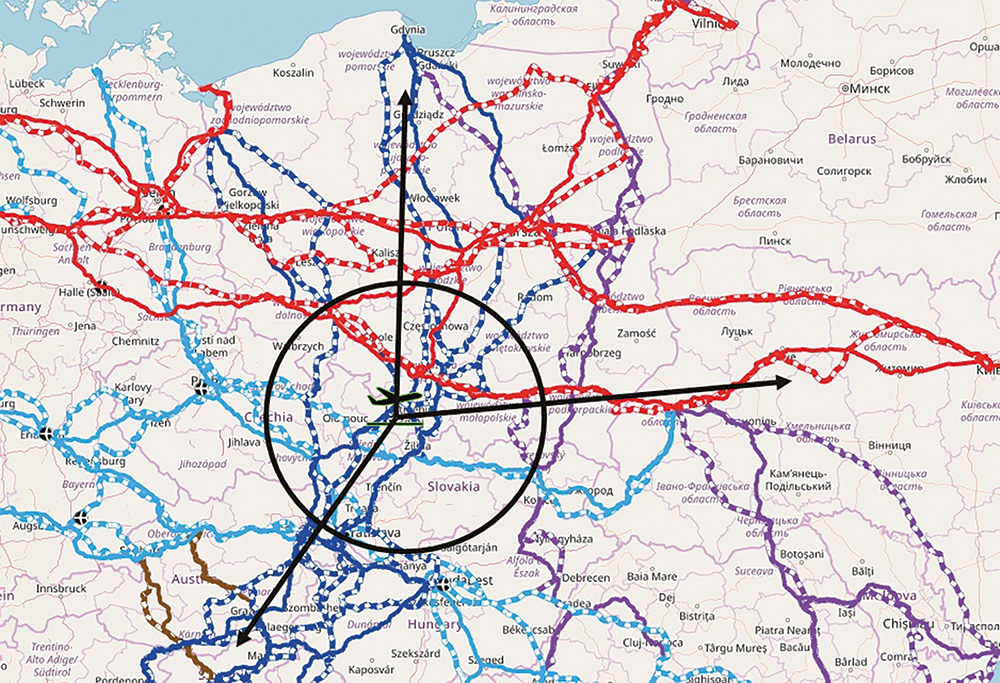

Ostrava’s strategic location at the crossroads of Europe underscores its vital logistical and military significance. © Google Maps and JAPCC

By developing Ostrava, US strategists could reshape NATO’s aerial footprint in the foothills of the wider Carpathians by offering American airpower a new operational axis toward Ukraine and become a ‘mini-Ramstein of Central Europe’ that would complement Poland’s growing airpower capabilities to forge a new aerial centre of gravity over East Central Europe that NATO currently lacks.

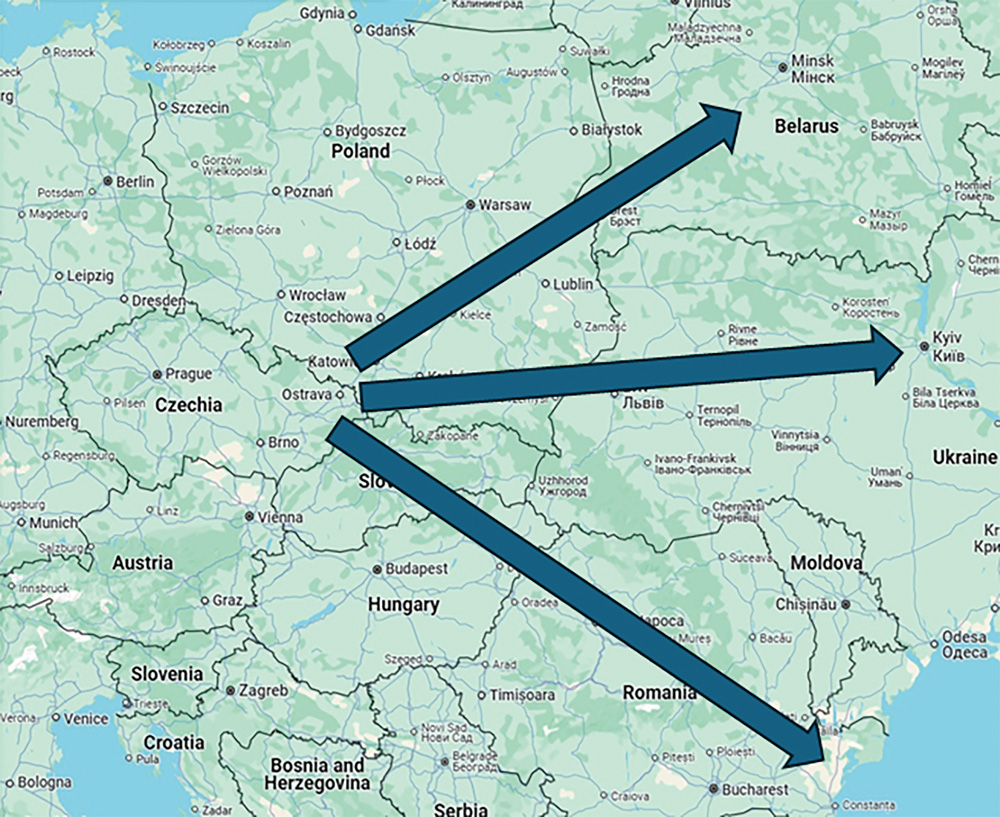

Ostrava is more than a civilian airport at the base of the Carpathian Mountains. It is also a key strategic road, air, and railway hub of two key European transport corridors as part of the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T). Two of those strategic transport corridors are interconnected with Ostrava, the Baltic Sea-Adriatic, and the Rhine-Danube corridors. Due to its unique location, Ostrava offers a commanding geographic location that enhances NATO mobility in an East-West direction and is well situated to help position NATO to counter a threat from either Belarus, Western and Central Ukraine and elsewhere from across the Eurasian steppe.

Lastly, another strategic dividend to using Ostrava is it would complement the existing but overtaxed NATO logistical node through Rzeszów in southern Poland. One of the new strategic realities of the war in Ukraine and how it has revolutionized NATO’s eastern flank is the emergence of Rzeszów as a key ground-based Line of Communication (LOC) to Ukraine via eastern Poland where an estimated 95 percent of all NATO arms deliveries to Ukraine pass. Often referred to as the ‘gateway to Ukraine’, Rzeszów and its airport, Jasionka, operate as both a civilian and a military rail and airport hub due to the city’s proximity to the Ukrainian battlefront. In the past three years Rzeszów has emerged as a key NATO supply line for munitions and other critically needed materiel being sent to Kyiv as part of the NATO assistance effort. Rzeszów offers important strategic significance due to its road and rail connections and greatly facilitates NATO logistical efforts to assist Ukraine’s war efforts.

Lviv, for example, is 50 kilometres from the Ukrainian border. In the past three years, the once quiet Rzeszów-Jasionka airport has become a key weapons hub for Ukraine but its airfield has limited capability to handle the large amounts of supplies destined for Ukraine that transit through it. Moreover, concern over Russia targeting Rzeszów-Jasionka has prompted German Defense Minister Pistorius to order the deployment of a German Patriot battery to protect the supply hub. In short, NATO should avoid putting all its ‘logistical eggs’ into one basket and should diversify its defensive posture in East Central Europe.

By upping its aerial footprint at Ostrava, NATO accomplishes several objectives at once. It not only reduces the flying distance between Joint Force Command (JFC) Brunssum and JFC Naples to the frontlines of Ukraine, but it could also strategically and economically integrate precarious NATO frontline member states, such as Slovakia, and Hungary, into the Alliance’s planning.

Ostrava is a vital strategic hub connecting road, air, and rail routes within the Trans-European Transport Network. © GISCO and JAPCC

Such a development could dampen their overly friendly ties with Moscow as a larger NATO presence at nearby Ostrava generates economic benefits to the surrounding regional economy. Whereas JFC Brunssum has been called the balcony of Europe, Ostrava could become NATO’s front door to the Carpathians and, by extension, provide NATO with a new window into Ukraine and diversify from its dependence on Rzeszów as its only logistical hub in the region and lessen its dependence on central Poland.

Conceptually, Ostrava could become a new symbol of NATO’s commitment to its Eastern Europe members by deepening its presence in the wider Carpathians as the war in Ukraine creates new NATO logistical corridors eastward toward Ukraine and Belarus. In addition, it also would help strengthen NATO’s political and economic influence over neighbouring Slovakia.

Politically, it would remind European policymakers that the US is not wedded to its old tidal infrastructure in Western Europe but is prepared to embrace a new common-sense approach to deal with its threats from the East. Creating a new airbase at Ostrava would also demonstrate that NATO is prepared ‘to balance one foot with another’ as it extends its aerial footprint further to the East to ward off Russian encroachment and improve its defensive posture toward Russia while simultaneously enhancing the security of Ukraine.

Perhaps more importantly, by creating an aerial bridgehead at Ostrava, the United States could reward Czech President Petr Pavel for his commitment to reach NATO’s two percent defence spending threshold and his determination to modernize his military, including his $7.5 billion investment to purchase American-made F35s. For the first time in 18 years, Czechia in 2025 reached the two percent threshold for yearly defence spending and will maintain this as a minimum level after passing a national law to ensure that the country’s defence spending never drops below two percent. Rewarding Czechia’s investments also signals to American allies in Western Europe that the United States is prepared to reward its Eastern European allies for their commitment to defend the Alliance while scaling down its presence in some countries to a shell of their former self and reconstitute this presence if needed.

Finally, the economic payoff for Czechia’s investment in Ostrava would result in a major boost to the local economy which has experienced a downturn in recent years. The Dutch economy around JFC Brunssum, for example, has benefited immensely from the NATO presence and generates over $131 million annually for the local community. Diversifying NATO’s logistical hubs is wise as the United States adjusts its strategic footprint more to ‘center field’ than the tidewater regions of Western Europe and solidifies support along three strategic axes in what is known as the Silesian belt comprising southern Poland, Czechia, and Slovakia.

It is time for NATO and US policymakers to think more contextually about how to use what Czechia can offer through its strategic location in East Central Europe and as a window into Ukraine. Developing an air base at Ostrava would also build upon Czechia’s existing and well-established logistical rail network to reconfigure NATO’s eastern flank to face the threat emanating from eastern Ukraine and the Black Sea.