Introduction

In Operation Allied Force, a moment of high-stakes survival unfolded that would shape NATO’s perspective of joint personnel recovery (JPR). On 2 May 1999, then-Lieutenant Colonel David Goldfein was flying his F-16 over hostile territory when a Serbian surface-to-air missile struck, compelling him to eject behind enemy lines. Isolated and vulnerable, Goldfein transmitted his famous plea, ‘Start finding me, boys.’1 What followed was a tense and methodically coordinated rescue mission – Operation Allied Force’s only successful conventional combat search and rescue (CSAR) mission. This singular event underscored the profound importance of JPR to the Alliance.

Today’s operational landscape differs from the challenges faced in 1999 Kosovo. Modern battlespaces are now dominated by sophisticated threat environments and advanced long-range missile systems. Over the same period, NATO’s necessary dedication to counter-insurgency (COIN) operations, compounded by evolving strategic priorities and resource pressures, has inadvertently eroded institutional knowledge of JPR in peer conflicts and diminished its overall emphasis. Consequently, if a pilot like Lieutenant Colonel Goldfein were isolated today, JPR forces would face immense challenges. The pervasive nature of advanced sensors, formidable integrated air defence systems, and contested airspace now demands a renewed and robust approach to NATO’s personnel rescue mission.

This article energizes the strategic commitment – moral, mental, and financial – to JPR, not specific platforms. It argues that NATO Headquarters, Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE), Joint Force Commands (JFCs), Theatre Component Commands, and member nations must significantly increase focus, funding, and dedicated personnel to enhance Alliance JPR capabilities. This investment is crucial for the moral duty to protect personnel, combat power reconstitution, and Alliance cohesion. To achieve this, NATO must reaffirm the core purpose of JPR investment, establish an integrated, institutional Joint Personnel Recovery Centre (JPRC), and revitalize isolated personnel (ISOP) recovery capability through investment, education, training, and exercises.

Organizational Gaps

Since 1999, several factors have eroded NATO’s JPR organizational structure and readiness. Adversary technological advances, a lengthy Afghanistan focus, and competing priorities reduced emphasis on JPR for high-intensity conflict. Many tactics, techniques, and procedures and equipment were designed for Middle East conflicts involving air supremacy against less advanced foes, leaving doctrine ill-suited for peer or near-peer threats. NATO’s many other priorities also demanded substantial resources.2 These constraints require careful rebalancing to ensure foundational, no-fail missions like JPR are not compromised.

In short, cumulative changes have weakened NATO’s JPR organizational structure and overall readiness. The Alliance must urgently train and stress its JPR C2 networks and recovery forces under anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) conditions, carefully balancing operational risk. JPR forces need exposure to these environments before an Article 5 scenario. NATO members must also procure interoperable JPR assets and technologies to ensure national efforts contribute effectively to collective capability. Without interoperability, the full potential of combined efforts is lost. Critically, NATO must establish a persistent, resourced JPR structure and conduct realistic exercises to ensure future isolated personnel like Goldfein return with honour.

Operational Guidance

JPR is a complex operation requiring joint, inter-allied, inter-partner, and often cross-government cooperation. Sustained multinational collaboration is essential to synchronize Alliance JPR efforts. In 2022, the Multinational Capability Development Campaign (MCDC), led by the US Joint Staff J-7, published ‘JPR 2040: A Global Perspective,’ highlighting strategic observations within JPR.3 The study identified themes including building a comprehensive PR mindset, expanding scope to new threats and environments, and accelerating technology adoption.4 The MCDC aimed to identify critical gaps in policy, doctrine, education, training, exercises, and evaluations facing future JPR challenges.

While the MCDC report effectively outlines the organizational gaps and operational challenges facing today’s JPR forces, it was intended as a diagnostic, not a prescriptive, document. This article builds on that foundation by proposing concrete solutions. NATO JPR stakeholders must act on these challenges proactively, before a crisis exposes shortcomings. The MCDC concluded that without adaptation, education, and realistic training, JPR forces will be unprepared for future conflicts.5

The Moral Imperative

The core argument for robust JPR capabilities is the moral imperative – an ethical contract and unwavering commitment between NATO leaders and personnel placed in harm’s way. Since ISOP accept significant risk for NATO goals, the JPRC, subordinate Personnel Recovery Coordination Cells, and tasked forces are responsible for their recovery. SHAPE, NATO’s highest strategic military headquarters, is responsible for safeguarding warfighters. The warrior ethos and commitment to ‘leave no one behind’ are fundamental military values shared across the Alliance.6

Failing to invest adequately in personnel recovery risks severely undermining service members’ trust in NATO leadership. Such failure sends a chilling message about how individuals are valued, which can harm recruitment, retention, and morale. Additionally, the psychological impact on deployed forces – aware of weak recovery capabilities – can reduce operational boldness and risk acceptance. Conversely, a strong JPR system signals firm commitment, boosting the psychological resilience of every soldier, sailor, and airman.

SACEUR’s vast area demands more rescue forces than any single entity can provide. A robust, Alliance-wide personnel recovery system – featuring effective C2 networks, rapidly deployable quick reaction forces (QRFs), and well-rehearsed CONOPS – reassures NATO personnel and their families they will not be abandoned.7 Personnel must be confident that capable JPR forces, with coherent C2, will exhaust every effort to bring them home.

Combat Reconstitution

From a realist, operational standpoint, the need for combat reconstitution and sustainment strongly justifies JPR investment. Reconstitution includes recovering personnel and reintegrating them into operations where their experience remains vital. Experienced personnel, especially with recent combat experience, are not easily replaced via standard training. Their knowledge, awareness, and decision-making are critical, particularly during Major Combat Operations (MCO). An ISOP’s value extends beyond morality to the Alliance’s investment in its training and unique combat experience. Every captured, wounded, or missing NATO service member risks the loss of essential expertise, intelligence, and combat power.

For example, the F-35 program exemplifies multinational cohesion and advanced capability, as showcased by the training for its skilled pilots. Training an F-35 pilot costs approximately €10 million and three years to achieve basic readiness – roughly the price of three main battle tanks – highlighting the value of such personnel.8,9,10 The same applies to experienced NCOs, SOF, intelligence specialists, and other key enablers whose expertise is hard to develop.

Improve Alliance Synergy

NATO’s 75th anniversary in 2024 demonstrated a unified alliance can sustain long-term peace and collective defence. Yet, the nature of warfare continues to evolve. Modern conflict is increasingly coalition-based, requiring unprecedented interoperability and ongoing combined training among allies. NATO leaders must see national forces as components of a collective structure, akin to the Allied Reaction Force (ARF), established in July 2024 to enhance deterrence.11 Improved readiness, standardized training, and greater cohesion build trust, reduce the impact of personnel losses during MCO, and strengthen collective political security.

A coherent and robust JPR framework strengthens multinational trust and cohesion by enforcing standardized training, ensuring equipment compatibility, and enabling essential intelligence-sharing. An effective JPR system depends on routinely exercised, enforced standards. NATO JPR guidance, found in Allied Joint Publication (AJP) 3.7, Recovery of Personnel in a Hostile Environment, often lacks the tactical-level detail needed for effective execution.12 For instance, no unified standard exists for survival gear, emergency radios, or signalling devices across NATO forces. These gaps create friction and delay recoveries – potentially costing lives. Incompatible communication systems hinder critical exchanges between ISOP, multinational recovery teams, and the JPRC, leading to breakdowns in mission information flow. NATO leaders must champion standardized JPR processes, equipment, and training at the unit level – before Article 5 is triggered – to reinforce Alliance trust and readiness for major combat operations.

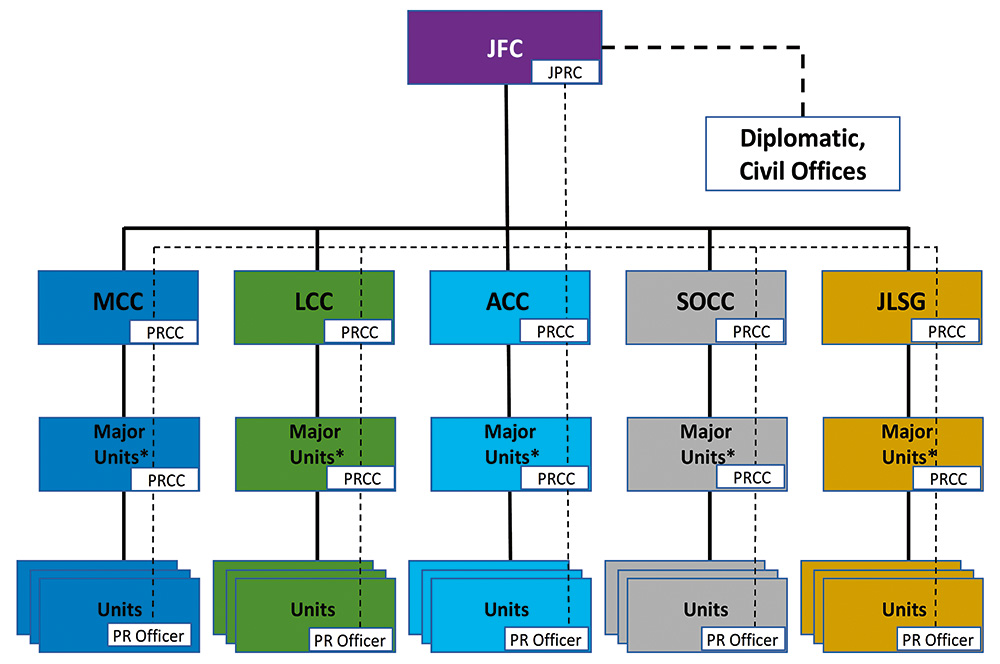

*Major Units: e.g. Corps, Division, Brigade, etc. and other services equivalents.

While the JPR organizational architecture is conceptually optimized for high-end warfighting, its peacetime implementation remains largely aspirational. The reliance on intermittent training and exercises, rather than persistent integration into baseline activities and current operations, has limited its practical utility and adaptability. © NATO

Establishing an Integrated JPRC

Allied Command Operations (ACO) leads Alliance missions, with SHAPE guiding three JFCs (Brunssum, Naples, Norfolk) and tactical commands (AIRCOM, LANDCOM, MARCOM). Throughout all these organizations, NATO lacks a single, dedicated institution responsible for the full JPR mission during peacetime. Instead, each of these five commands handles its own JPR activities. In crises, JPR responsibility typically shifts to a designated JFC and its ad hoc JPRC, which is often staffed informally by untraining personnel.13

No single NATO organization formally owns or champions JPR; responsibility remains dispersed under SHAPE’s guidance. AIRCOM often serves as a key stakeholder and de facto SME hub, since many JPR functions like CSAR align with air operations and fall under the Military Committee Standardization Board.14,15 Yet, the current Allied Joint Publication (AJP) 3.7 primarily covers CSAR – a vital, but incomplete, aspect of JPR. This leaves NATO without comprehensive joint doctrine for all JPR facets, such as non-conventional recovery or operations in denied areas where CSAR is impractical. Such a doctrinal gap has aggravated knowledge loss and hindered the shift from COIN to peer-conflict JPR.

To fix systemic issues, NATO should create a persistent, integrated JPRC as the central hub for doctrine, planning, and advocacy at SHAPE for strategic alignment. This JPRC needs a dedicated multinational SME staff covering all JPR disciplines (C2, intelligence, SERE, etc). JFC Brunssum – responsible for much of Central and Northern Europe and collective defence planning – is well suited to host it. In peacetime, it would develop doctrine, share lessons, source and prepare gear, and lead education and training. In crises, it would coordinate complex cross-area operations with expertise that ad hoc teams lack. Without this, the five commands lack a standardized, refined C2 function for full-spectrum JPR.

Investment in JPR Readiness

NATO’s fragmented JPR efforts have sometimes weakened interoperability and readiness in multinational operations. No unified training syllabus or education program covers all NATO JPR forces across components, even for conventional CSAR. Groups like the Tactical Leadership Program (TLP), European Personnel Recovery Centre (EPRC), and European Air Group (EAG) play key roles in training, especially in the air domain, but are not formally within the NATO Command Structure. This can cause gaps in standardization and strategic alignment with SHAPE.16 These organizations typically use AJP-3.7 as a foundation for CSAR training but generally don’t cover the full JPR spectrum, including unconventional recovery or inter-agency coordination.

To provide a coherent JPR strategy and enhance readiness, the first step is establishing the aforementioned integrated JPRC as a focal point for JPR doctrine and advocacy. Subsequent efforts for a ready NATO JPR force must focus on education, training, and exercises:

Education: Many personnel retain a COIN-era JPR mindset (e.g., assuming air supremacy, neutral civilians). Forces need updated JPR education for peer A2/AD environments. This training must also cover the information warfare aspect, where adversaries may exploit ISOP for propaganda.

Training: While NATO air forces develop JPR skills through programs like TLP and the Air-Centric Personnel Recovery Operatives Course (APROC) at the EPRC, these focus mainly on traditional CSAR. Future training must cover multinational complexities, first responder integration, and non-traditional recovery methods.17 Scenarios should include denied environments, advanced electronic warfare, and degraded C2.

Exercises: SHAPE-led exercises like STEADFAST DUEL, BALTOPS, and other major drills are necessary to test JPR functions at operational and strategic levels.18 Exercises need challenging, JPR-focused objectives stressing the system; simple CSAR scripts are insufficient. NATO must prioritize JPR C2 resilience, interoperability, and decision-making under pressure before acquiring new assets. Without an integrated, trained JPR structure, even top CSAR platforms cannot overcome fractured C2. Exercises should also test deconfliction with other operations, managing multiple ISOP, and integrating non-military recovery options.

Conclusion

NATO leaders must re-energize JPR as a foundational NATO mission to ensure an isolated individual’s worst day is not their last. Failing to adapt JPR would imperil future isolated personnel, like Lieutenant Colonel Goldfein, and erode the Alliance’s core strengths. A revitalized JPR capability is paramount because it upholds our unwavering moral contract with service members, fortifying their morale and resolve; it is crucial for reconstituting invaluable combat power and sustaining operational effectiveness; and it powerfully reinforces Alliance cohesion, deepening trust and bolstering collective security.

To achieve this, NATO must act decisively: establish an integrated, persistent JPRC with clear advocacy at SHAPE, and renew focus on comprehensive JPR doctrine, education, realistic multinational training, and demanding, large-scale exercises. Only through these efforts can NATO ensure ‘that others may live,’ safeguarding its greatest asset – its people – and maintaining its credibility as a defensive Alliance.19 The time for incremental adjustments is over; a strategic reset for NATO JPR is essential.