Introduction

Even though NATO currently recognizes the Electromagnetic Environment (EME) as an operating environment,1 the latest Libya operations and the Syrian conflict battlespace highlighted that coalition forces might be required to operate within an extremely complex environment in future battles, where the Electromagnetic Spectrum (EMS) might be considered as the fundamental domain of operations. It may be the domain that bridges all the other operating domains allowing the commanders to attain a level of electromagnetic dominance that enables effective employment of more conventional domains in the battlespace. Further, Electronic Warfare (EW) concurrently denies neutralizes, disables or disrupts an adversary’s use of the EMS over the area of operations.

On the other hand, in the modern warfighting discipline of EMO, EW is not the only stakeholder of the EME. New capabilities have emerged and are now operating in the EME alongside traditional EW disciplines. In this context, NATO has introduced the concept of EMO, and the Alliance’s nations have agreed,2 that EMO are all activities that shape or exploit the EME for attack or defence including the use of the EME to support operations in other environments.3

Cyberspace4 – which is also a key stakeholder of the EME – has already been declared by NATO as a separate domain of operations which NATO must be prepared to defend as effectively as it does the domains of Air, Land, Maritime and Space.5 Nonetheless, some NATO nations have already recognized the convergence between Cyberspace and EW activities6 and highlighted them under the concept of Cyber-Electromagnetic Activities (CEMA).7 This synergy has already been effectively employed during Operation Atlantic Resolve.8 The symbiotic relationship between EW and cyber warfare has also been noted by near-peer competitors of NATO such as Russia, China and Iran. In particular, it is highly likely that Russia’s EW and Cyber capabilities have been merged.9

While the NATO Framework for Future Alliance Operations (FFAO) highlights the need of operations and effects across all the domains in pursuit of future NATO forces’ utopia of Multi-Domain Operations (MDO). The ‘Alliance Joint Electromagnetic (EM) Strategy’ recognizes the necessity of synergy through greater integration of the EME core functions and related activities such as Cyberspace and Space. This begs the question related to NATO’s desire to achieve electromagnetic superiority on the modern battlefield: ‘Does NATO need a holistic approach towards integrating all EMS disciplines under a single operating domain in order to achieve the ambitious goal of true MDO?’

Full-Spectrum Dominance Requires Harmonization of EM Disciplines in the Campaign Plan

During the escalation of the Battle of Britain during World War II, the Prime Minister of Great Britain, Winston Churchill, highlighted10 that dominance in the Land and Maritime domains requires dominance in the Air first: today that dominance is required not only in the Air but also in Space.

Apart from the prerequisite of air dominance over the battlefield, the latest NATO Strategic Foresight Analysis (SFA) highlights that the future physical environments will evolve towards large urban areas, usually near oceans and more significantly in the developing regions, which will amplify the potential for instability and conflicts.11 Emerging technologies and the exploration opportunities offered by climate change, along with constant demand on energy resources, contribute to the Arctic region becoming increasingly open to a range of activities such as oil, gas and mineral exploration and leisure activities by Arctic and non-Arctic nations. This access into the Arctic Region increases the likelihood of future conventional military interventions. As a consequence, a NATO coalition force may be tasked in the future for joint operations either in an urbanized geographical area or in an Arctic environment. Hence, battles may encompass a variety of missions, where the increased collateral damage challenges, targeting issues and extreme climate conditions may dictate the compulsory use of non-lethal12 effects and the non-kinetic13 weapons of NATO’s arsenal.

In the Libya campaign, NATO forces operated in a contested and congested urban environment and the victory against Qaddafi forces was greatly enabled by the use of Air Power.14 Even though air operations were the main effectors in the Libya conflict, they were not abundant. The Libya urbanized battlefield showed that the usage of non-lethal and limited-lethal activities such as: Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR), EW and precision strikes with low yield effects were essential in minimizing fratricides and civilian casualties, and proved to be critical warfighting factors for future NATO military interventions.

Similarly in the Syrian conflict, it was shown that air superiority was not achieved without having dominance of the EME. Russia demonstrated in Syria, and in the Crimea annexation, that EME capabilities are an integral part of Russian armed forces’ modern military strategy.15 The battlespace in Syria highlighted that advanced Russian EW effects combined with the new sophisticated strategic long-range Surface-to-Air Missile (SAM) system (S-400 Triumf) has brought NATO’s ability to achieve air dominance into question.

The differences in the Libyan and Syrian conflicts could be omens, foreshadowing that in the future NATO will only achieve dominance in the Land, Maritime, Air, and Space domains, if the EME elements and functions such as EW, SIGINT and Cyber can be superior by demonstrating synergistic and harmonized activities.

The Common Ground of EM Disciplines Reflects the Need for Synchronization

In the future, NATO will undoubtedly be employed in an expeditionary warfare scenario somewhere around the rapidly-changing world. The rapid pace of technology evolution and the increased use of Commercial Off-The-Shelf (COTS) solutions by near-peer adversaries and non-state actors has allowed them to develop a range of capabilities in the EME for use in symmetric and/or asymmetric military activities. Systems like advanced sophisticated radars and SAM systems are employed in new ways for faster targeting, the fusion of multiple sensors, the creation of unexpected waveforms and operations across the EMS. These adaptations make them harder to detect and jam, or even regain superiority from the adversaries in the ‘occupied’ EMS frequencies.

The dominance in the EME may not be achieved unless the EMS capabilities and activities are integrated into a single and unique domain of operations. The EMS stakeholders16 such as Cyberspace, EW, Signal Intelligence (SIGINT), and Battlespace Spectrum Management (BSM) must be unified to an integrated Cyber-EM domain of operations, since Cyberspace was declared a domain of operations during the Warsaw Summit17 in July 2016. Current NATO Cyberspace policy remains focused on Defensive Cyber Operations (DCO) and has not yet embraced Offensive Cyber Operations (OCO), though it has developed a framework mechanism for integrating cyber effects provided voluntarily by its Allies. While NATO Cyber experts and legal advisors are very slowly considering the implications of pursuing OCO, near-peer competitors have likely developed doctrine to employ cyber effects, integrated and synchronized with EW and SIGINT activities in their military operations.

Cyberspace18 is the only domain which has been physically and virtually created by humans employing applications of the EME (e.g. copper wires, fibre optic cables, and microwave and satellite relays) rendering it a part of EMS as well. The apparent common ground which is shared by Cyberspace and EMS fields has been previously acknowledged by United States (US) Army. A US Army study concluded that EW, SIGINT, and Cyberspace could and should share the same staff, processes, and technologies to avoid duplication of effort and to prevent working at cross-purposes.19 Cyberspace operations overlap with more than 50 percent of EW and SIGINT activities necessitating the great need for operational consolidation.

The perfect example of the EW and Cyberspace interdependency was clearly highlighted during a September 2007 Israeli strike on a North Korean supported nuclear weapons facility in Syria. In particular, a cyber-attack was delivered by an Israeli airborne electronic attack platform, which allowed Israeli forces to virtually take control of the Syrian integrated air and missile defence system, and let the ‘highly observable’ F-15s and F-16s strike aircraft penetrate the Russian-designed, modern and long-range SAM systems of Syria.20 This effect could be called a form of ‘cyber-stealth’.

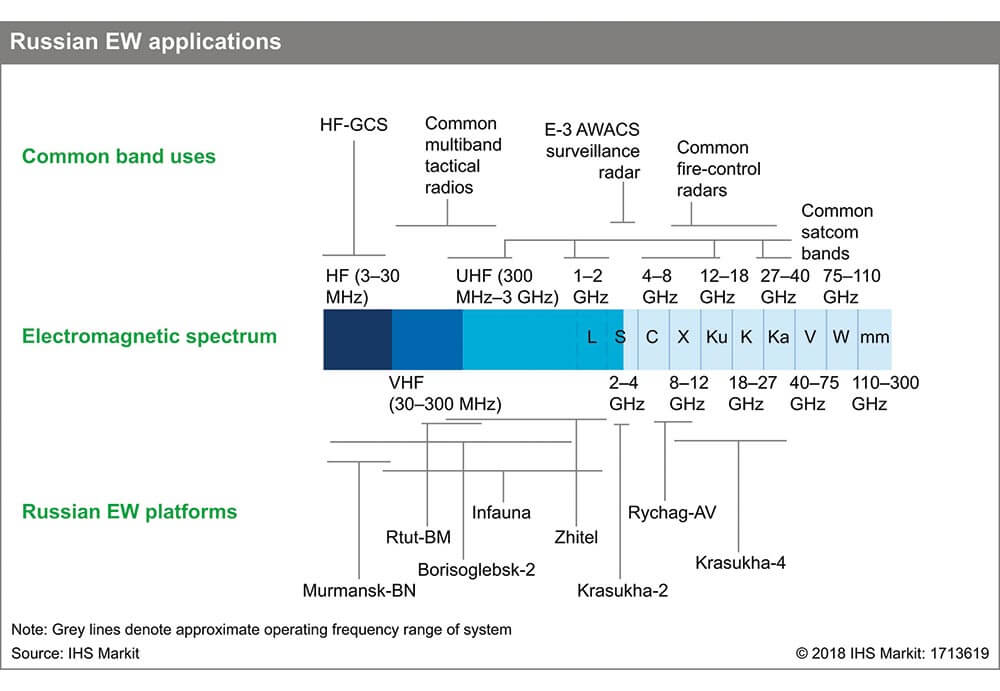

In contrast, the Russo-Georgian wars’ lessons learned motivated Russia to develop tremendous and modern EW capabilities to counter NATO EMS capabilities. Looking at the figure on page 74, Russia, is not only looking to deny NATO use of the EMS, but also has employed its EW capabilities in eastern Ukraine and Syria as ‘test beds’ for refining their tools. In a similar way, the Russian-Ukraine clash (2014–present) has become a Russian Cyber doctrine ‘test bed’21 as well. Russia even employed its cyber-attack capabilities on the Syrian battlefield and demonstrated that cyber is an attractive and low-cost tool for power projection, allowing Russian armed forces to deliver low signature effects without fighting in the Forward Edge of the Battle Area (FEBA).

Dominating in the ‘Blizzard’22 of EMS

In addition to Russia’s resurgence, for the first time, the Secretary General recently addressed that the rise of China also poses challenges for Alliance security and he stressed that ‘as the world changes, NATO will continue to change’.23 Consequently, technological advancements such as artificial intelligence, autonomy, and quantum computing, coupled with increased future urbanized areas, will result in operations being conducted in a uniquely contested, congested, complex, and constrained battlespace. Further, operations in extreme climates will trigger an increasing competition among major and resurgent powers across the globe for accessing and governing the EMS ‘blizzard’. While NATO planners are pursuing the utopia of MDO, presently no one domain can be the single dominant user of the EME, unless NATO political and military leaders recognize the emerging threat within EME to concentrate efforts into one domain, in order to meet the world’s future security challenges. This includes:

Integrating and harmonizing the EM disciplines into the Cyber-Electromagnetic Domain. The great need to employ non-lethal effects on future battlefields in support of MDO effectiveness guarantees the necessity of coherent EMS employment. By unifying the EME stakeholders and challenging them to coordinate and collaborate as a single task force under one policy, doctrine and strategy, NATO forces could dominate in both, the physical (Land, Air, Maritime/Littoral and Space) and the non-physical (Information, Cyberspace and EM) operating domains. Thus, Alliance forces may deliver Offensive, Defensive and ISR synchronized CEMA across the domains in support of future NATO campaigns.

Increasing decision speed and capacity. EME warfighting entities generate, in most cases, non-lethal effects by employing the EMS ‘blizzard’. The future battlefield environment, in which the EM effects will be delivered at the speed of light, will create a foggy EME and coalition decision-makers at all levels will be incapable of taking timely decisions or executing the right courses of action in support of a campaign’s desired end state without some form of assistance. Consequently, emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and big data management/fusion should be employed to support the decision-making capacity of Allied leaders, so that NATO forces can acquire the particular EME threat, deny or neutralize it and if necessary, deliver a counterstrike.

Employing the EMS to increase the resiliency. What is old is new again. NATO should exploit certain regions of the EMS such as acoustic, visual and infrared to develop capabilities, enabling NATO forces to be less observable, and increase NATO infrastructure resilience. Advanced camouflage techniques, radar-absorbing materials, decoys or even acoustic sensors and passive radars could be some of the technologies employed to increase the resilience of NATO infrastructure.

In conclusion, future battlefield conditions and security challenges will necessitate the treatment of the EMS as a domain of operations rather than an environment. The EMS is the cross-domain and fundamental glue which binds the other operating domains of Air, Land, Maritime, Cyber, and Space. Integrating the EMS disciplines, functions and related activities into a coherent system will allow armed forces to dominate the EMS ‘blizzard’ and enable NATO to truly execute the perfect MDO that meets modern-day challenges.