Introduction

As airmen and soldiers working in a joint force environment, various definitions and associations come to mind when discussing the extensive and historically important topic that entails the military effects of Air-Land Integration (ALI). ALI refers to the synergistic employment of lethal and non-lethal effects by Air and Land forces to meet a Commander’s intent. More importantly, inherent to this definition of ALI is the critical coordination and understanding required between both Air and Land forces to maximize effects on a target and mitigate the risks to friendly forces. Categorized as a ‘Comprehensive-Strategic-Concept’, ALI ranges from tactical to strategic level processes aimed at seamlessly combining Air and Land forces’ capabilities to achieve joint operational objectives. This description of ALI did not evolve overnight but, over the decades since the dawn of military aerial capabilities which were showcased in World War I. For the first time, that war saw the use of aircraft in a major conflict providing relatively long-range bombing and target spotting for artillery forces to refine firing onto an enemy position in support of ground troops. From the First World War to the modern conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, there has been extensive coverage on the significance of ALI and how the effective employment of ALI created the military advantages that made the difference.1 Famous is the statement made by General Bernard Montgomery after ‘Operation Compass’ in World War II: ‘If you can knit up the power of the Army on the land and the power of the air in the sky, then nothing will stand against you and you will never lose a battle.’2

Since its debut, ALI has always played an important role in the outcome of military conflicts. Subsequently, it is easy to hypothesize that future Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) will further stress the need for interoperable proficiency in ALI capabilities as a driving factor. It is essential to reflect on what common doctrine, policies, and possible solutions should be pursued by the Alliance to expand and update its ALI capabilities. The joint education and training of its forces are, and will continue to be, the fundamental building blocks for establishing proper tactics, techniques and procedures in MDOs. Despite recognizing the value in the education and training of its forces, NATO currently has a very limited number of formal joint education and training programmes that persistently prepare and cultivate a joint-minded force. Maintaining the current model of stove-piped educational programmes for single component forces is akin to maintaining an unprepared joint force. This ‘educational isolation’ creates a key strategic issue for the planning and execution of joint force operations.

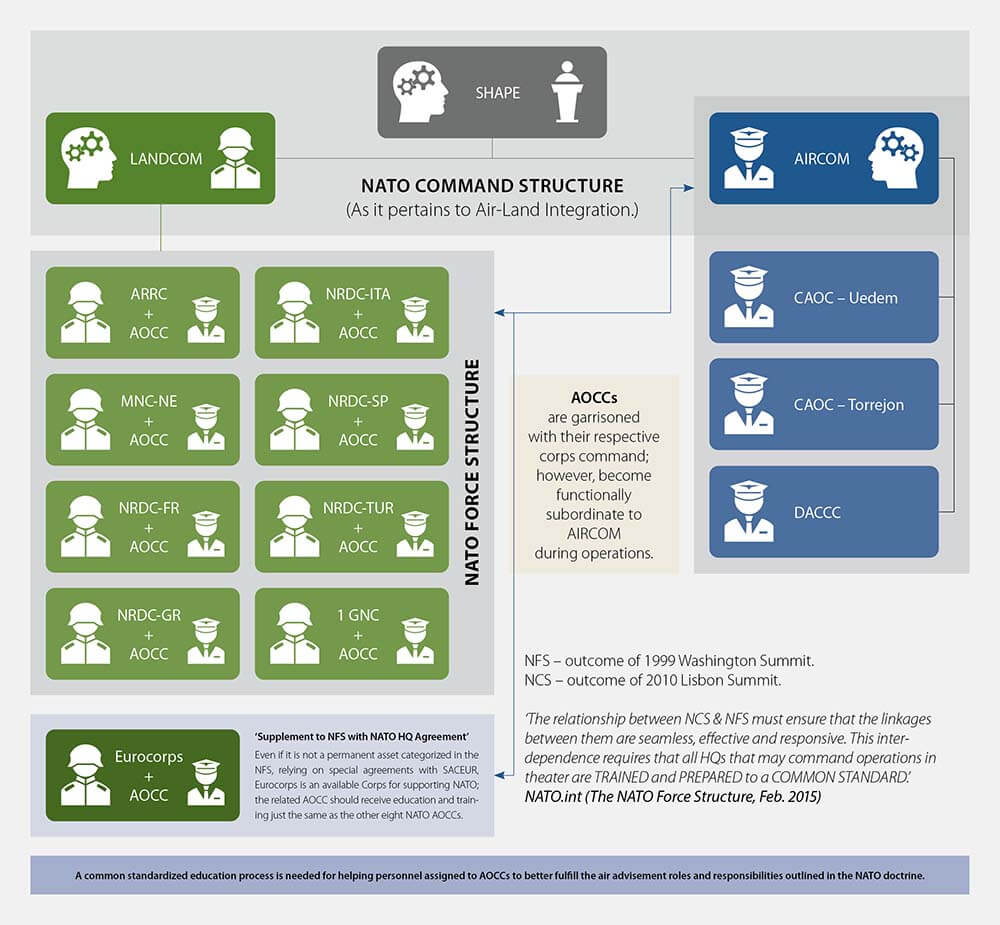

Origin of Air Operations Coordination Centres – A Joint Seam for Air-Land Operations

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, NATO underwent a major restructuring and reorganization of its forces. Prior to the post-Cold War changes, NATO’s Force Structure Air Operations Coordination Centres (AOCCs) were still attached to a land corps, however, they were known as Air Support Operations Centres (ASOCs). During NATO’s transition from nuclear deterrence to conventional deterrence, ASOCs were tasked to provide mobile tactical air control system facilities in support of air operations management for the self-sustaining Forward Air Component Command, Control, and Communications Concept.3 Moreover, the Air Component’s Command and Control (C2) plans included integrating offensive air support/interdiction operations with forward-deployed NATO forces operating through ASOCs and respective Tactical Air Control Parties (TACP) collocated with ground forces.4 These roles and responsibilities have remained primarily associated with today’s United Kingdom (UK) and United States (US) national ASOCs, however, these roles are not applicable to NATO’s existing AOCCs, despite contradicting allied doctrine. Although current NATO doctrine conveys the best practices of a national ASOC assumed under the roles and responsibilities of an AOCC, it does not accurately reflect today’s reality, specifically regarding the staffing, training, and equipping of NATO’s eight active AOCCs.

Discovering the Reality of Overestimated Doctrinal Capabilities

NATO’s Allied Joint Publication (AJP) 3.3 (B) for Air and Space operations defines the AOCCs as an ‘air entity functionally subordinate to the Joint Force Air Component (JFAC) that is collocated with and is an integral part of an army corps …’ It further states that AOCCs provide air expertise and integrates the liaison and coordination functions relating to air operations. Specific to operations and exercises, AOCCs will provide execution-level coordination of air operations in support of the ground commander, as an extension of the JFAC.5 In a subsequent doctrine revision released in 2019, the extensive Allied Tactical Publication (ATP) 3.3.2.1 (D) mentions that AOCC processes are in close coordination with the corps Joint Fires Support Element (JFSE). These processes include: handling immediate (air) support requests, coordinating the execution of scheduled and on-call Close Air Support (CAS) sorties, and coordinating manned/unmanned aircraft transiting through airspace over the ground force commander’s operational area.6 In addition, the ATP describes that AOCCs, ‘when delegated the authority, can re-task/re-role/re-direct airborne assets, provide target updates, and launch ground alert aircraft on call for the ground manoeuvre commander, as required’.7 Notably, there is an indicated interchangeability between national/coalition ASOCs with the roles and responsibilities of AOCCs. Although ASOCs are not an organic NATO capability, the ATP states in particular cases, ASOCs may exist in place of the AOCC. Despite the doctrine describing that AOCCs are as capable of the aforementioned roles and responsibilities, there is no specific joint education and training provided to AOCC personnel to be able to perform as advertised. Since 2017, through ALI workshops and conferences with AOCC and joint fires personnel, a team of Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) on ALI at the DACCC and NATO Rapid Deployable Corps-Italy (NRDC-ITA) discovered that the divergence between AOCC capabilities from doctrine stems from a variety of issues. Primarily, the lack of standardized joint education and training of the personnel assigned to conduct Air-Land Operations. As a result, AOCC capabilities have not been exercised properly, leaving them to atrophy to a detrimental level. Frankly put, if NATO were to engage in major joint operations tomorrow, AOCCs could not be employed in the manner which current allied joint doctrine prescribes.

Trending issues gathered from various ALI workshops and conferences highlight that AOCCs have limited understanding on the ‘why and how’ of their prescribed doctrinal functions, while corps regularly misconstrue what AOCCs do and why they are co-located with them. Since AOCCs are not empowered by standardized education and training to perform their doctrinal roles, they are systematically overlooked or incorrectly employed by both Air and Land leadership. Consequently, the potential for improving NATO Air-Land operations is lost if key joint units, such as AOCCs, are left to determine their raison d’être. Perhaps, with consistent dialogue and engagement beyond the annual Trident series exercises, leaders from Allied Air Command (AIRCOM) and Allied Land Command (LANDCOM) can collectively gain traction for implementing mutually beneficial joint education and training opportunities for their forces. If NATO wants to ensure successful joint operations, it must solicit, advocate for, and endorse proposed improvements by subordinate units that bolster the joint education and training of its forces. Military success relies on a joint effort and providing proper joint education and training is the common foundation needed for authentic improvement of ALI at all levels, especially at the strategic and operational level, where the bulk of NATO forces function.

Evolution of a Solution – DACCC’s ALI Workshop

In the early stages of fielding NATO’s enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) mission, visiting senior officials received several questions and ideas regarding the potential joint integration of eFP battle groups and air support from the Baltic Air Policing (BAP) mission. Though the requirements to integrate two different NATO missions are highly complicated due to the politics involved, the basic ALI question still remained, how would a NATO-led joint operation on the Baltic and Polish front really work? To further explore this concern, the former Commander of the DACCC, present at the official eFP field visit, solicited his experienced instructors to determine feasibility of developing an educational programme that would familiarize rotating eFP forces with NATO joint doctrine. As the department head for JFAC Training8, providing initial functional education and training for all operations personnel in NATO’s Air C2 structure, the DACCC9 is well-versed in developing and presenting educational programmes. A team of DACCC instructors with ALI experience rose to the challenge by creating the ALI workshop to familiarize eFP and supporting forces with NATO joint doctrinal organization, procedures, and processes. Knowing a single-service cannot present a genuine joint education programme, the DACCC teamed up with Land component joint fires SMEs from NRDC-ITA and Multinational Corps Northeast (MNC-NE) to form the Air-Surface Integration Team (ASIT). Since November 2017, the ASIT has conducted six ALI workshops, catering to a training audience across NATO and national tactical-to-strategic level joint forces. These workshops included key personnel supporting eFP, whom had dealings with integrating CAS and/or joint fires. Using the breadth of experience and expertise shared by the training audience during each workshop, juxtaposed with existing NATO doctrine and force organization, the ASIT was able to gauge the depth of NATO’s joint ALI struggles. It became obvious, that ALI knowledge gaps did not solely exist amongst eFP rotational forces, but amongst NATO assigned forces writ large. As a result, the ASIT amended each subsequent ALI workshop curriculum to better educate and help fill these common knowledge gaps deemed crucial to conducting safe and effective joint Air-Land operations. The value of this new joint workshop spread fast, as each one grew in size to a maximum of 21 participants. Several ranking members from AIRCOM, LANDCOM, along with some AOCC Chiefs who attended, praised the DACCC’s innovative initiative on providing ALI education in a joint forum. Post-workshop surveys indicated 96 percent of the participants would recommend the joint education forum because it taught relevant and valuable information on ALI operations. Information they wished they had received upon arrival to their joint assignment and/or prior to participating in NATO joint exercises.

© JAPCC

Advocacy for Joint Education in NATO

Fundamental education programmes for joint forces are NATO’s low-risk and low-cost preparation option to keep pace with increasingly rapid changes and anticipated threats inherent to joint all-domain operations. While NATO boasts an extensive menu of 824 courses under its Education and Training Opportunities Catalogue (ETOC)10, none are tailored to educate forces specifically on ALI operations. With this in mind, NATO must continually assess, adapt, and prepare its forces to combat an array of anticipated threats. More specifically, NATO leaders should regularly assess and associate their strategic concerns down to tactical problems because it may be that some seemingly tactical solutions, such as a joint education programme, will help produce solutions needed to alleviate their strategic concerns. This is why the DACCC ASIT has taken the initiative to refocus, standardize, and advance its legacy ALI workshop to propose it as a NATO-selected joint educational course. The new course is geared towards better preparing the airmen and soldiers assigned to support ALI operations, especially those assigned to AOCCs, joint fires support elements and other joint liaison roles. The utility of a joint education programme will prove most valuable for NATO forces, as it not only provides them with useful information, it cultivates trust and joint personnel relationships which are essential for operating in a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous strategic environment.

Formalizing Joint Education with Functional AOCC Integration Training

In close collaboration with AIRCOM HQ and the expanded network of ALI stakeholders in NATO, the DACCC is building on its successful ALI workshops by developing a week-long course called Functional AOCC Integration Training (FAIT). The new course is designed to help standardize the knowledge base across AIRCOM and LANDCOM personnel who will work in AOCCs, Joint Fires Support Elements (JFSE), and joint liaison roles. It will incorporate two days of academics on Air and Land processes and capabilities, one day of joint planning for movement into phase three operations, one day of joint ALI operations execution, and one day of joint lessons learned and doctrine discussion. FAIT will be presented as a pilot-course later this year to key ALI stakeholders for vetting and validation. If FAIT is well received, the follow-on progression of implementation is to align it with the second week of the DACCC’s existing and successful Initial Functional JFAC Training (IFJT). Doing this will further develop applicable communication skills and joint relations by exposing liaisons and personnel from Air Operations Centres (AOCs), AOCCs, and the Land component to actual coordination requirements, during the Air C2 operations planning and execution phases. Although the DACCC has taken an initiative in improving joint education for ALI, there are other, and perhaps better-suited institutions such as, the NATO School or Centres of Excellence that could fully undertake the aforementioned joint educational task. To help bridge such a transition, NATO could designate a central executive steering group to provide guidance and obtain results in improving joint synergy and interoperability for all of its components.

Conclusion

To ensure feasibility in advancing MDO interoperability in NATO, joint proficiency in ALI mission capabilities must first be attained. To do this, NATO must provide a unified strategic vision for increasing joint operations proficiency through joint education. Integral tasks to achieve joint proficiency, current educational programmes and doctrine must be scrutinized and revitalized accordingly. Implementing standardized joint educational programmes, specifically aimed at the units with liaison roles, such as AOCCs, will help prevent significant divergence between published joint doctrine and the reality of capabilities. The DACCC’s initiative in developing and formalizing a course for AOCCs, liaisons, and Land component personnel is but one building block of many required to improve joint force interoperability in NATO. Accordingly, it is of strategic importance that each component seeks innovative opportunities to educate one another, so the sum of their capabilities equals a much stronger military alliance. Strategic alignment happens through consistent dialogue and engagement. The conversation to improve joint operations must be organization-wide, interconnected, and collaborative for joint integration to be a success. Ultimately, persistent preparation of joint forces, ranging from the tactical to strategic levels, through standardized education and training programmes, will help cultivate a joint-minded force to ‘lift and shift’ its capabilities as one, across all domains.